Van Gogh – L’uomo e la terra

La mostra presenta una lettura dell’opera di Van Gogh del tutto inedita e si focalizza sulle tematiche legate a Expo 2015 per comprendere ed esplorare il complesso rapporto tra uomo e natura, fatica e bellezza.

Comunicato stampa

Il 23 febbraio del 1952 a Palazzo Reale di Milano inaugurava la prima grande mostra su Van Gogh. Virgilio Ferrari era il Sindaco della città, e Caio Mario Cattabeni Presidente del Comitato Esecutivo della mostra e Assessore all’Educazione del Comune di Milano. Le opere provenivano in gran parte dal Kröller-Müller Museum di Otterlo. Il pubblico era in delirio, come riporta la stampa dell’epoca.

Dopo 62 anni di distanza le opere di uno degli artisti più famosi al mondo tornano a Palazzo Reale per la mostra “Van Gogh”, promossa dal Comune di Milano - Cultura, prodotta e organizzata da Palazzo Reale di Milano, Arthemisia Group e 24 ORE Cultura - Gruppo 24 ORE.

L’esposizione, realizzata anche grazie al sostegno del Gruppo Unipol, è patrocinata dall’Ambasciata del Regno dei paesi Bassi a Roma e inserita negli eventi ufficiali del Van Gogh Europe, l’istituzione di recente costituzione, sostenuta dal governo olandese a tutela e promozione dell’opera di Van Gogh.

La mostra presenta una lettura dell’opera di Van Gogh del tutto inedita e si focalizza sulle tematiche legate a Expo 2015: la terra e i suoi frutti, l’uomo al centro del mondo reale, la vita rurale e agreste così strettamente legata al ciclo delle stagioni.

In un’epoca in cui la maggior parte degli artisti rivolgeva lo sguardo al paesaggio urbano, frutto dell’industrializzazione europea della fine del XIX secolo – come accadeva appunto per i Neo-Impressionisti Seurat e Signac – Van Gogh sposta la sua attenzione verso il paesaggio rurale e il mondo contadino, ritenendo la vita semplice della campagna, un soggetto dotato di una nobile e sacra accezione, e dove chi lavora la terra diventa una figura eroica e gloriosa.

La vita e le mansioni della tradizione agreste diventano per lui materia di studio: dai primi disegni fatti in Olanda, fino agli ultimi capolavori dipinti nei pressi di Arles, Van Gogh esprime la propria affinità verso gli umili, immedesimandosi con loro, e rappresentando la loro dignitosa natura.

Kathleen Adler, esperta del periodo impressionista, curatrice di mostre dedicate ad alcuni tra i più importanti esponenti di questo movimento artistico, nonché autrice di significative monografie, è la curatrice della mostra ed è stata supportata nel suo lavoro da un comitato composto da alcuni tra i più noti e riconosciuti esperti di Van Gogh e della pittura del periodo: Cornelia Homburg, massima esperta dell’opera di Van Gogh nonché curatrice delle più importanti mostre dedicate all’artista; Sjraar van Heugten, già Head of Collections al Van Gogh Museum di Amsterdam, Jenny Reynaerts Senior Curator 18th and 19th Century Paintings al Rijksmuseum di Amsterdam; Stéphane Guégan, Conservatore del Dipartimento di Pittura al Musée d’Orsay.

Il lavoro curatoriale ha permesso di costruire un percorso che accompagnerà il visitatore attraverso oltre 50 lavori dell’artista, alla scoperta di opere note e di altre mai viste prima, per comprendere ed esplorare il complesso rapporto tra uomo e natura, tra fatica e bellezza, rivivendo i molteplici stati d’animo che Vincent Van Gogh ha trasferito indelebilmente nelle sue creazioni.

Il corpus centrale della mostra è costituito, come per l’esposizione del 1952, da opere provenienti dal Kröller-Müller Museum di Otterlo a cui si aggiungono lavori provenienti dal Van Gogh Museum di Amsterdam, dal Museo Soumaya-Fundación Carlos Slim di Città del Messico, dal Centraal Museum di Utrecht e da collezioni private normalmente inaccessibili: un’occasione unica per approfondire, attraverso gli occhi dell’artista, il complesso rapporto tra l’essere umano e la natura che lo circonda.

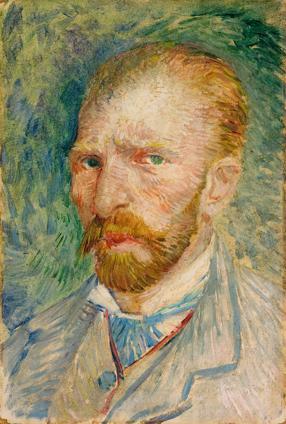

Tra i capolavori concessi dal Kröller-Müller Museum alla mostra milanese, citiamo L’autoritratto del 1887, il Ritratto di Joseph Roulin del 1889, Vista di Saintes Marie de la Mer del 1888, la Testa di pescatore del 1883 e Bruciatore di stoppie, seduto in carriola con la moglie del 1883.

L’esposizione godrà di una mise en scène d’eccezione: l’archistar giapponese Kengo Kuma, classe 1954, curerà il progetto di allestimento della mostra.

VAN GOGH

Man and the Earth

curated by Kathleen Adler

18 October 2014 – 8 March 2015

Milan, Palazzo Reale

PRESS RELEASE

Man, who never ceases searching within himself and the world around him in a sort of mute and terrible question like that which emerges from a face, painted on a canvas and containing “the question” encompassing human existence.

The earth, which, in the end, is the only response for those who feel alienated and marginalized by a pragmatic society which values work only for its capacity to generate profit and which rejects anyone who questions the condition and fate of humanity, precisely because he has succeeded in unmasking its guilty conscience.

This is the theme and purpose of the exhibition ‘Van Gogh. Man and the Earth’, which opens on 18 October 2014 at Palazzo Reale di Milano (until 8 March 2015): a journey into the world of art, but above all into the existential philosophy of the great Dutchman, which represents a perfect corollary to the theme of the 2015 Expo – Nourish the Planet.

A philosophy which, as Giulio Carlo Argan wrote, “stands alongside that of Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky, taking the side of the deprived, of the peasants from whom industry took not only the earth and bread, but also the dignity of human existence, the feeling of the integrity and religiosity of work.”

The exhibition – sponsored by the Milan City Council - Culture, produced and organized by Palazzo Reale in Milan, Arthemisia Group and 24 ORE Cultura - Gruppo 24 ORE¸ in collaboration with the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Netherlands and made possible also thanks to contributions from the Gruppo Unipol – will include the self-portrait of Vincent – with “the tense, almost aggressive expression and awe-inspiring gaze” of someone who is not defeated, despite being cast to the margins by the world, in the darkness of the mental asylum, and who silently screams to the world his anger, his complete solidarity with the outcasts of the Earth, like a crucified but indomitable Christ. It will also offer a series of oils and drawings that complete the full immersion into the rural cycle, as in the circle of human life: peasants, landscapes of the cold North and the sunny South, snapshots of life, still lifes, vases of flowers – unique and precious tiles of a single mosaic, because as he wrote his brother Theo: “In a painting, I’d like to say something consoling, like a piece of music. I’d like to paint men and women with that je ne sais quoi of the eternal.”

The exhibition is part of ‘Milano Cuore d’Europa’ (‘Milan, Heart of Europe’), the multidisciplinary cultural programme devoted to the European identity of our city, also through personalities and artistic movements whose stories and work contributed to building the citizenship and cultural dimension of Europe.

The core of the exhibition consists of works from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Netherlands, with additional pieces from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the Museo Soumaya-Fundación Carlos Slim in Mexico City, the Centraal Museum in Utrecht, and private collections normally unavailable to the public. The exhibition therefore represents a unique opportunity to deepen, through the artist’s eyes, one’s understanding of the complex relationship between man and the nature that surrounds him.

In the six sections of the exhibition, visitors will be able to observe and identify with the life and strain of the fields through drawings, including Peasant Woman, Binding Sheaves, but who also gathers and hoes. Drawing was a much-loved technique that allowed Van Gogh to affirm: “to study and draw all that belongs to peasant life...I am no longer so powerless before nature as I was once”, before becoming completely immersed in the landscape, coloured in oil like a revelation experienced by the artist upon arriving in Provence (“The Mediterranean has a colour like mackerel, in other words, changing – you don’t always know if it’s green or purple – you don’t always know if it’s blue – because a second later, its changing reflection has taken on a pink or grey hue”). This can be seen in the exhibition in pieces like View of Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer, Olive Grove with Two Olive Pickers or The Green Vineyard.

And also portraits because, as he wrote in June 1890, “There are modern heads that one will go on looking at for a long time, that one will perhaps regret a hundred years afterwards.” Faces like those of Joseph-Michel Ginoux or Joseph Roulin (on display in the exhibition), about which Argan wrote: “Where, then, is the tragic in the portrait of the postman Roulin? Not in his serene pose... Art becomes, as Pavese would have said, the ‘craft of living,’ and this is the craft through which Van Gogh tries desperately to counter the mechanical work of industry, which is not living.”

In the peasant world, in the simple and pure beings like that postman who visited him every day in the asylum and sang ‘La Marseillaise’, Van Gogh searched for the meaning of life and things. He found it in exertion, in hard work. Like the farmers and fishermen he portrayed because, as he always wrote to his brother, his favourite correspondent, “The rest of us should grow old working hard, and there’s why we get depressed when things don’t go our way.”

Work that was never rewarded, as it was impossible to understand at the time its completely new lines and style, despite the influences of and relationships with the Impressionists and the beloved Milles and Daumier, strengthened by the reading of contemporary novelists (as evidenced by a remarkable essay in the catalogue – edited by 24 Ore Cultura – by Stéphane Guégan) who were also too ahead of their times.

The curator of the exhibition, Kathleen Adler, an expert on the Impressionist period who has curated exhibitions on some of the most important exponents of this artistic movement and authored significant monographs, worked on all of this to choose the pieces to be displayed. She was helped in this process by a committee composed of some of the most renowned experts on Van Gogh and painting in this period: Cornelia Homburg, one of the foremost Van Gogh’s scholars and curator of the most important exhibitions dedicated to the artist; Sjraar van Heugten, former Head of Collections at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam; Jenny Reynaerts, Senior Curator of 18th- and 19th-Century Paintings at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam; Stéphane Guégan, Curator of the Painting Department at the Musée d’Orsay.

The design of the exhibition, sponsored by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Rome and inserted into the official events of Van Gogh Europe, the recently established institute sustained by the Dutch government for the protection and promotion of Van Gogh’s work, has been entrusted to architect Kengo Kuma. Kuma was chosen not only for his status as a starchitect of world fame, but also because he is a child of the Japanese culture that Van Gogh so loved, a respectful and original culture centred around the Earth. And so is Kuma: original but at the same time respectful of the great Dutchman’s artistic philosophy as well as the intentions of the producers and the curator. His work will not fail to amaze visitors, completely immersing them in the theme of the show, where they will find themselves going beyond the world that “never sees or respects the ‘human’ in the human being, but only the greater or smaller value of the money and goods he bears this side of the grave. The world takes no account at all of the other side of the grave. This is why the world sees no further than the end of its nose” (from a letter to Theo, 15 May 1882).