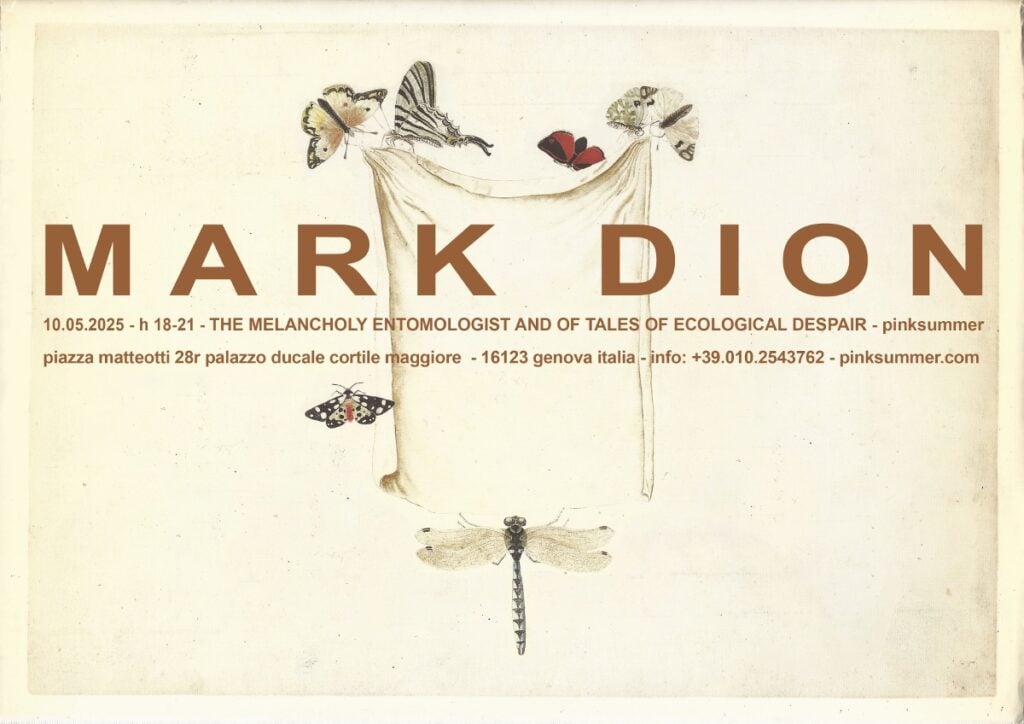

Mark Dion – The Melancholy Entomologist And Of Tales Of Ecological Despair

Mostra personale.

Comunicato stampa

Chapter I

DDT

Pinksummer: Riflettere sull’etica dell’amore per tutte le creature in tutti I suoi dettagli questo è il difficile compito assegnato al tempo in cui viviamo”, scrisse il medico musicologo Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965). Primavera Silenziosa, Silent Spring il titolo originale, il libro manifesto antesignano del Movimento Ambientalista della biologa Rachel Carson è dedicato a Schweitzer e alla sua speciale concezione dell’etica. Pubblicato nel 1962, Primavera Silenziosa fu una vera e propria denuncia rispetto all’uso dei pesticidi e degli erbicidi, è grazie anche al libro se nel 1972 fu vietato negli Stati Uniti l’uso del DDT; l’insetticida venne proibito in Italia nel 1978.

Carson si chiede perché in quei tardi anni ’50 le voci di primavera, insetti, uccelli tacessero in molte contrade dell’America. Prosegue esplorando gli effetti devastanti del DDT che oltre a danneggiare la fauna, distrugge l’intero equilibrio ecologico delle acque e del suolo e conclude “I pesticidi sono proprio necessari?”. La scoperta del DDT fu attribuita nel 1939 al chimico svizzero Paul Hermann Müller, che fu insignito del Premio Nobel per la medicina nel 1948 “per la scoperta della grande efficacia del DDT come veleno da contatto contro molti artropodi”.

Cosa ha rappresentato il DDT, il primo insetticida moderno, per l’umanità di quell’epoca calda e positivista?

Mark Dion: Ciò che rappresentava era il controllo della natura.

Come gran parte del pensiero positivista del dopoguerra in ambito scientifico, compresa la “Green Revolution”, l’idea di una vita migliore attraverso la chimica. (Lo slogan attuale della DuPont Corporation era “Better Things for Better Living....Through Chemistry”). L’idea che il bene pubblico potesse essere servito dall’applicazione di nuove generazioni di sostanze chimiche, tra cui fertilizzanti, biocidi, composti resistenti all’acqua, lubrificanti, è rimasta in gran parte invariata fino a quando Rachel Carson e altri hanno esaminato gli effetti collaterali ecologici indesiderati dell’applicazione massiccia di sostanze chimiche industriali nel tempo.

Mentre si parlava molto di controllo della natura al servizio dell’uomo, la realtà era che queste innovazioni erano profondamente al servizio del capitalismo prima e del benessere umano poi, e non del benessere ecologico. In tutto il mondo si è consolidato un modello di utilizzo della scienza (chimica, ingegneria, silvicoltura, pianificazione urbana, ecc.) per ottenere vantaggi economici e sociali a breve termine, ignorando le conseguenze a lungo termine sull’ambiente e sulla salute pubblica.

Rachel Carson è davvero una delle autentiche eroine del XX secolo. Scrittrice di talento, scienziata intransigente e dotata di un coraggio e di una pazienza incredibili, ha combattuto una battaglia senza precedenti contro l’industria e lo Stato. Naturalmente aveva ragione sul DDT e su altri veleni ambientali, ma ha dovuto resistere agli attacchi dei dirigenti dell’industria corrotta, dei politici e della stampa. Questi ultimi erano spietati nel loro vetriolo, spesso francamente misogino. Rachel Carson ha prevalso e ha inaugurato una nuova generazione di ambientalisti e di protezione dei luoghi selvatici e della salute pubblica.

Inutile dire che i pesticidi sono una necessità per la salute pubblica e per l’agricoltura come la pratichiamo oggi. I biocidi devono essere considerati come una soluzione di ultima istanza e le conseguenze a lungo termine della loro applicazione devono essere comprese a fondo e il costo per l’ecosistema deve essere considerato di primaria importanza. In Occidente abbiamo imparato che non ci si può fidare del fatto che le persone che sviluppano questi rimedi chimici si autocontrollino e che si debba sempre considerare che il profitto prevale sulla sicurezza.

Chapter II

Body Horror – Cinema e letteratura entomologici

PS: Rispetto al genere del body-horror, gli insetti la fanno da padroni sia direttamente che mediatamente. Muovendo da La Metamorfosi di Franz Kafka, passando da La Mosca, il film uscito nel 1986 di David Cronemberg interpretato da Jeff Goldblum, fino a Lo Scarafaggio di Jan Mc Ewan del 2020, considerato un pamphlet politico omaggio a La Metamorfosi. A differenza del mutante Gregor Samsa di Kafka che si risveglia insetto gigantesco, il Jim Sans di Mc Ewan “un tipo perspicace, ma niente affatto profondo”, dopo una notte di sogni inquieti si risveglia primo ministro d’Inghilterra. Jim diventato umano ci mette pochissimo, a differenza di Gregor inizialmente assai impacciato come insetto, a imparare a muovere le mani, a salire le scale con solo due piedi e soprattutto a comprendere efficacemente l’uso di Twitter.

Seth Brundle protagonista di La Mosca, la cui mutazione non è repentina, ma progressiva, a differenza di Gregor e Jim, al di là dei peli irsuti che gli crescono sulla schiena, si accorge che qualcosa in lui sta cambiando perché si sente più forte, resistente e sessualmente più prestante e siccome quando il corpo muta anche la mente lo segue, diventa sempre più arrogante. Sia Seth, che il Gregor di Kafka, I due protagonist che si trasformano in insetto, passano dalla paura alla curiosità e la mutazione a tratti viene vissuta come una sorta di liberazione.

La letteratura e il cinema entomologico rappresentano il complesso rapporto tra l’uomo e gli insetti? L’insetto rappresenta l’altro da sé, fino a contenere addirittura elementi alieni in rapporto alla percezione umana?

MD: L’insetto è l’altro per eccellenza. Gran parte dell’essere dell’insetto è un’irritazione per la moderna sensibilità urbana di essere al di là della natura.

Parte del disgusto articolato nelle fiction che tu citi riguarda gli aspetti inquietanti dell’architettura corporea degli insetti: troppe zampe, un diverso tipo di simmetria, strani cicli di vita trasformativi, abitudini alimentari voraci, un altro tipo di riproduzione. Forse ancora più inquietante è l’idea che gli insetti ci ricordino, che anche noi siamo animali coinvolti in una complessa rete di vita che non riusciamo a controllare completamente. Ogni scarafaggio in cucina, puntura di zanzara, pidocchio nella classe di un bambino ci ricorda che non abbiamo ancora trasceso la natura. Naturalmente odiamo che ci venga ricordato che siamo animali, perché ci ricorda anche che siamo mortali.

Quindi, quando parliamo di preoccupazione per il collasso della popolazione di insetti, può essere difficile convincere il grande pubblico. Molti risponderanno: “Che liberazione”, perché non si rendono conto di quanto la vita sulla Terra dipenda dagli invertebrati. Certo, è facile motivare le persone a salvare i panda, gli elefanti e i delfini (sopravvivenza dei più carini), anche se non stiamo facendo un buon lavoro, ma è difficile motivare le persone a preservare il numero delle popolazioni di insetti. Per molti gli insetti sono sinonimo di parassiti, nonostante il fascino di lucciole e farfalle.

Chapter III

Pasolini e la scomparsa delle lucciole

PS: Se Mc Ewan ha scritto Lo scarafaggio nel 2020 contro la Brexit, Pier Paolo Pasolini sulle pagine del “Corriere della Sera” nel 1975, usò la metafora della scomparsa delle lucciole per sferrare un violento attacco alla Democrazia Cristiana, l’allora partito di maggioranza in Italia. Pasolini inizia distinguendo il Fascismo fascista dal Fascismo democristiano, che ritiene responsabile del repentino declino morale del popolo Italiano, trasformatosi in bravissimo tempo in un popolo di consumatori, dimentichi di ogni valore che li aveva connotati fino allora (patria, famiglia, religione, risparmio): “(…) Quel fenomeno che è successo in Italia una decina di anni fa. Nei primi anni ’60 a causa dell’inquinamento dell’acqua (gli azzurri fiumi, le rogge trasparenti) sono cominciate a sparire le lucciole. Il fenomeno è stato fulmineo e folgorante. Dopo pochi anni le lucciole non c’erano più”. Pasolini conclude con la frase “Darei l’intera Montedison per una lucciola”, Montedison è stato un gruppo industriale Italiano dedito alla chimica e all’agroalimentare.

Gli insetti di fatto sono forti indicatori rispetto alla salute dell’ambiente, Pasolini riconduce l’inquinamento della natura al decadimento morale e questa analogia potrebbe essere applicabile alla sofferenza delle api mellifere o a altre specie di insetti impollinatori circa l’azione umana. Dante nella Divina Commedia cita spesso gli insetti e se nel Paradiso (XXXI canto), compara il tripudio degli angeli a una “schiera d’api che s’infiora”, nel canto III dell’Inferno gli ignavi, tra cui il papa Celestino V che aveva abdicato, vengono tormentati nudi da mosconi e vespe, fino a sanguinare. Dante è morto di malaria, peraltro.

Nell’antichità l’invasione di locuste o di altri insetti infestanti veniva percepita di fatto come sinonimo di decadimento morale dell’uomo.

Cosa pensa l’entomologo malinconico rispetto a queste analogie che dall’ambiente naturale scorrono fino al decadimento morale umano in questo nostro mondo in cui il capitalismo globale stracinico è diventato turbo e sovranazionale?

MD: Il fenomeno del collasso delle popolazioni di insetti è un esempio paradigmatico del rapporto suicida dell’Occidente con la natura. Gli strumenti di questo suicidio non sono rasoi, revolver, pillole o binari del treno, ma una miriade di fattori che vanno dai pesticidi all’inquinamento luminoso, fino all’uso scriteriato del territorio e all’inquinamento. Il fattore trainante non è la depressione e la disperazione, ma il capitalismo estremo.

La spinta a proteggere gli insetti non è semplicemente estetica o etica, per quanto questi fattori siano preziosi, ma è soprattutto essenziale per la sopravvivenza. Dobbiamo proteggere gli insetti per autoconservazione. Gli insetti forniscono così tanti servizi ecologici, dall’impollinazione al cibo per i vertebrati come gli uccelli, fino all’essere essenziali nel processo di circolazione dei nutrienti e dell’energia.

Vivere negli Stati Uniti in questo momento significa assistere al trionfo dei valori del capitalismo estremo su tutti gli altri sistemi di valore. L’unico sistema di valori in vigore sembra oggi essere quello del denaro e del potere, del guadagno a breve termine e dell’affare più vantaggioso. Le conseguenze di questo sistema di valori intensamente antisociale si riflettono nella rottura dell’etica e nell’ascesa dell’autoritarismo, con risultati profondi e perniciosi. Parte di questa cultura del capitalismo bruto è anche la rottura della razionalità e il rifiuto della ricerca scientifica a lungo termine. Senza una ricerca ambientale impegnata a lungo termine è impossibile comprendere la portata del degrado ecologico.

Parte dell’aspetto malinconico del nostro entomologo è che la portata della catastrofe ambientale è schiacciante. Ho letto molto sul tema dell’“apocalisse degli insetti” e mi sono interessato ad alcuni aspetti della situazione. Il primo è che il fenomeno è stato identificato per la prima volta da dilettanti e non da entomologi che lavorano per lo Stato, l’Università o un museo. Mi è piaciuto molto il fatto che questo sembrasse un ponte con lo studio della storia naturale vecchio stile, in cui la scienza dei cittadini giocava un ruolo così importante. Un’altra cosa che mi ha ispirato è stata l’internazionalità e la cooperazione della disciplina, con scienziati e dilettanti che condividono informazioni in tutto il mondo. Sono stato molto influenzato dal profilo di Elizabeth Kolbert sul dottor David Wagner, biologo degli insetti dell’Università del Connecticut. Poiché dal mondo degli studi sugli invertebrati arrivano poche buone notizie, lo immaginavo necessariamente malinconico. Ironicamente, quando l’ho incontrato mi ha detto che non era malinconico, ma piuttosto eccitato e attivo. Ha detto che è il momento di agire e di impegnarsi e che non c’è tempo per la malinconia. Pur essendo d’accordo, penso anche che il lutto sia una risposta appropriata a questo momento e che non escluda assolutamente l’azione.

Chapter IV

Insetti cibo del futuro

PS: E cosa pensa il tuo protagonista entomologo, quando gli viene annunciato con tracotanza che gli insetti saranno il nostro cibo del futuro?

Di quali insetti si parla? Considerando che in questi ultimi decenni gli insetti si sono ridotti dell’80% e egli sa che gli insetti sono l’architrave della biodiversità: sono consumatori e cibo per gli uccelli e i rettili e senza insetti non ci sarebbe più il 70% delle specie vegetali che conosciamo.

C’è qualcuno che invoca anche nella postmodernità il ritorno del DDT per sconfiggere la zanzara anofele in Africa, responsabile della malaria.

MD: Da tempo si chiede di utilizzare gli insetti come cibo in futuro. Sembra che si tratti di un gruppo piuttosto ristretto di insetti da consumare, che comprende grilli e cavallette. Questo potrebbe risolvere alcuni problemi proteici dell’uomo, ma non avrà alcun impatto sulla diversità degli insetti, se non quello di liberare terreni ora utilizzati per il bestiame e per le colture alimentari.

Considerando l’interconnessione delle cose, un forte calo di una popolazione di organismi è motivo di preoccupazione. Altri vertebrati sussistono grazie al consumo di insetti: uccelli, pesci, rettili e molti mammiferi. Numerose piante dipendono dall’impollinazione degli insetti. Come tu dici, molti insetti sono specie indicatrici, che ci danno un’idea della salute ambientale più ampia di un ecosistema. Quando riceviamo messaggi di feedback così chiari dal mondo che ci circonda, è a nostro rischio e pericolo ignorarli.

Non vedo un ritorno generalizzato al DDT o almeno non agli eccessi del suo uso precedente. La battaglia con la zanzara Anopheles è un esempio di evoluzione in corso. Man mano che applichiamo nuove tecnologie di esclusione, controllo biologico e chimico, la zanzara si evolve costantemente per ostacolare i nostri sforzi di estinzione. Se da un lato è sorprendente vedere la rapidità con cui l’evoluzione può agire, dall’altro è grave che le zanzare trasmettano l’organismo che causa la malaria, che colpisce decine di migliaia di persone.

Chapter V

Il Giardino del diavolo

PS: A proposito della biodiversità e delle monoculture, nelle foreste pluviali, altamente a rischio umano, dell’Amazzonia, zone biodiverse per eccellenza, ci si imbatte a volte in zone misteriose, in cui la biodiversità scompare, e lì si ergono solo alberi di Duroia hirsuta. Le popolazioni locali chiamano queste aree Devil’s garden. La responsabilità della monocoltura della Duroia hirsuta non è di uno spirito maligno bensì di una specie di formica, la Mymelachista schumanni che fa il nido nel tronco di questo albero, uccidendo con dosi letali di acido formico ogni altra specie vegetale in queste aree, in tal modo la formica assicura alla propria colonia una quantità abbondante di siti per nidificare. Un beneficio a lungo termine, considerando che le colonie di Mymelachista schumanni possono vivere fino a 800 anni. Il comportamento della formica limone non è terribilmente simile rispetto alla nostra agricoltura intensiva? Potrebbe vivere il pianeta Terra, se venisse trasformato in un immenso Devil’s garden?

MD: Forse la domanda dovrebbe essere: varrebbe la pena vivere su una Terra che fosse solo un Giardino del Diavolo? Forse questi formicai sembrano particolarmente spaventosi perché vediamo noi stessi, nel nostro immenso potere di trasformazione, riflessi in essi.

Sono molto attratto da parabole ecologiche come quella del Giardino del Diavolo. Quando ho iniziato a fare il tipo di lavoro che faccio oggi, alla fine degli anni Ottanta, molte delle mie sculture e installazioni prendevano spunto da questi racconti di calamità ecologiche. Era più o meno il momento in cui il termine Biodiversità stava entrando nell’uso comune. È un’idea così bella e potente, che indica la varietà e la variabilità della vita sulla Terra. Credo che la scoperta del concetto di biodiversità abbia in qualche modo dato un senso alla mia pratica artistica. Con tanti artisti della mia generazione, è facile capire a cosa siamo contro, essendo così critici, ma non è sempre facile capire a cosa siamo a favore. Io sono per la biodiversità.

La storia del Giardino del Diavolo è una grande illustrazione delle conseguenze impreviste della distruzione ambientale. Una volta che qualcosa viene degradato e poi lasciato libero di riprendersi, non c’è garanzia che le cose che ritornano siano le stesse che c’erano all’inizio. Qualcosa tornerà, ma probabilmente non quello che c’era prima. Lo stesso vale per la pesca. Se si prendono tutti i pesci, alla fine qualcosa tornerà a riempire la nicchia vuota, ma spesso non esattamente lo stesso pesce.

Chapter VI

Donald Trump insetto inconscio

PS: In questi tempi si fa tanto parlare di Trump e dei suoi dazi che fanno tremare I mercati dall’est all’ovest, percorrendo il globo in senso divisivo. Non sarebbe strambo se il tuo entomologo producesse un sogno del genere body-horror, trasformando il discusso presidente americano in un insetto. Che insetto con nome latino potrebbe essere quello sognato dalla creatività inconscia dell’entomologo malinconico?

MD: È un insulto al mondo degli invertebrati chiamare Trump insetto. Persino un virus non merita l’indegnità di essere paragonato al Presidente. Molto peggiore della narrativa body-horror è la cultura del sadismo e dell’ingiustizia che quotidianamente sfila sugli schermi americani.

Forse, se dovessimo dargli un nome latino binomiale, potrebbe essere Necrophorus Rex. Re dei morti.

Ringraziamenti:

Grazie a Monica Rivera per le sue preziose ricerche

Un grazie speciale alla Strega del Castello

per aver condiviso con noi alcuni dei segreti del suo mondo incantato

////////

Press release in form of interview

Chapter I

DDT

Pinksummer “To reflect on the ethics of love for all creatures in all its details this is the difficult task assigned to the time in which we live,” wrote musicologist physician Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965). Silent Spring the original title, the forerunner manifesto book of the Environmental Movement by biologist Rachel Carson is dedicated to Schweitzer and his special conception of ethics. Published in 1962 Silent Spring , it was a true denunciation with respect to the use of pesticides and herbicides , and it is also thanks to the book that in 1972 the use of DDT was banned in the United States, the insecticide was banned in Italy in 1978.

Carson wonders why in those late 1950s the voices of spring, insects, birds were silent in many quarters of America. He goes on to explore the devastating effects of DDT, which not only harms wildlife but also destroys the entire ecological balance of water and soil, and concludes, “Are pesticides really necessary?”

The discovery of DDT was attributed in 1939 to Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1948 “for the discovery of the great efficacy of DDT as a contact poison against many arthropods.”

What did DDT, the first modern insecticide, represent to humanity in that hot, positivist era?

Mark Dion: What it represented was the control of nature.

Like much of the post war positivist thinking around science, including the “Green Revolution”, the notion of better living through chemistry. ( The actual slogan of the DuPont Corporation was “Better Things for Better Living….Through Chemistry”). The idea that public good could be served by the application of new generations of chemicals including, fertilizers, biocides, water resistant compounds, lubricants, was largely unchanged until Rachel Carson and others looked at the undesirable ecological side effects of the massive application of industrial chemicals over time.

While there was a lot of lip service to the control of nature in the service of humankind, the reality was that these innovations where profoundly in the service of capitalism first and human welfare second, and ecological well being not at all. All over the world, a pattern became well established of using science (chemistry, engineering, forestry, urban planning, etc.) for short term economic and social gain, while ignoring long term environmental and public health consequences.

Rachel Carson is truly one of the legitimate heroes of the 20th Century. A gifted writer, uncompromising scientists and blessed with amazing courage and patience, she fought an unprecedented battle with industry and the state. She was of course correct about DDT and others Environmental poisons, but she had to withstand attacks from dirty industry executives, politicians and the press. They were mercilessly in their vitriol, which was often frankly misogynist. She prevailed and ushered in a new generation of environmentalists and protections for wild places and public health.

Needless to say, pesticides are a necessity with regards to public health and agriculture as we practice them today. Biocides should be thought of as a last resort solution, and the long term consequences of their application must be throughly understood and the cost to the ecosystem considered paramount. We have learned in the west that the people who develop these chemical fixes can not be trusted to police themselves and must always be regarded as putting profit over safety.

Chapter II

Body Horror - Entomological Cinema and Literature

PS: With respect to the body-horror genre, insects take center stage both directly and mediately. Moving from Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, via David Cronemberg’s 1986 film The Fly, starring Jeff Goldblum, to Jan Mc Ewan’s 2020 The Cockroach, considered a political pamphlet homage to The Metamorphosis. Unlike Kafka’s mutant Gregor Samsa, who wakes up a giant insect, Mc Ewan’s Jim Sans, “a perceptive fellow, but not at all profound,” wakes up after a night of restless dreams as prime minister of England. Jim turned human takes very little time, unlike Gregor initially quite clumsy as an insect, to learn to move his hands, climb stairs with only two feet, and above all to effectively understand the use of Twitter. Seth Brundle, the protagonist of The Fly, whose mutation is not abrupt but progressive, unlike Gregor and Jim, beyond the shaggy hairs growing on his back, notices that something in him is changing because he feels stronger, more resilient, and sexually more performant, and since when the body changes the mind also follows, he becomes more and more arrogant. Both Seth and Kafka’s Gregor, The two protagonists who transform into insects, move from fear to curiosity, and the mutation at times is experienced as a kind of liberation.

Do entomological literature and cinema represent the complex relationship between humans and insects? Does the insect represent the other than itself, even to the point of containing alien elements in relation to human perception?

MD: The insect is the ultimate other. So much of insect’s being, is an irritant to the modern urban sensibility of being beyond nature. Some of the disgust articulated in the fictions you mention relates to the uncanny aspects of insect body architecture- too many legs, a different kind of symmetry, strange transformative lifecycles, voracious eating habits, another kind of reproduction. Perhaps even more unsettling is the notion that insects remind us that we are also animals implicated in a complex web of life, which we just can’t seem to entirely control. Every cockroach in a kitchen, mosquito bite, head louse in a child’s classroom, reminds us that we have not yet transcended nature. Of course we hate to be reminded that we are animals because it also reminds us that we are mortal.

So when we speak about being concerned about insect population collapse, it can be a hard sell to a general public. “Good riddance”, many will respond, since they don’t realize how utterly dependent life on earth is on invertebrates. Sure it is easy to motivate people to save pandas, elephants and dolphins (survival of the cutest), although we are still not doing a very good job, but is difficult to motivate people to preserve insect population numbers. For many insects are synonymous with pests, despite the appeal of fireflies and butterflies.

Chapter III

Pasolini and the Disappearance of the Fireflies

PS: If Mc Ewan wrote The Cockroach in 2020 against Brexit, Pier Paolo Pasolini in the pages of “Corriere della Sera” in 1975, used the metaphor of the disappearance of the fireflies to launch a violent attack on the Christian Democrats, the then majority party in Italy. Pasolini begins by distinguishing Fascist Fascism from Christian Democrat Fascism, which he holds responsible for the sudden moral decline of the Italian people, transformed in a very short time into a people of consumers, forgetful of every value that had connoted them until then (homeland, family, religion, savings): “(...) That phenomenon that happened in Italy about ten years ago. In the early 1960s due to water pollution (the blue rivers, the clear irrigation ditches) fireflies began to disappear. The phenomenon was lightning fast and dazzling. After a few years the fireflies were gone.” Pasolini concludes with the phrase “I would give the entire Montedison for a firefly,” Montedison was an Italian industrial group dedicated to chemistry and agribusiness.

Insects in fact are strong indicators with respect to the health of the environment, Pasolini traces the pollution of nature to moral decay, and this analogy could be applicable to the suffering of honey bees or other species of pollinating insects about human action. Dante in the Divine Comedy often mentions insects, and if in Paradise (Canto XXXI) compares the jubilation of the angels to a “host of bees bursting into bloom,” in Canto III of Inferno the sloths, including Pope Celestine V who had abdicated, are tormented naked by flies and wasps until they bleed. Dante died of malaria, by the way. In ancient times, the invasion of locusts or other insect pests was actually perceived as synonymous with man’s moral decay.What does the melancholic entomologist think about these analogies flowing from the natural environment to human moral decay in this world of ours in which global extracinic capitalism has become turbocharged and supranational?

MD: In the phenomenon of insect population collapse we have a paradigmatic example of The West’s suicidal relationship to the nature world. The instruments of this suicide, are not razors, revolvers, pills or train tracks, but a myriad of factors from pesticides and light pollution, to unwise land use and pollution. The driving factor is not depression and hopelessness but extreme capitalism.

The drive to protect insects is not merely aesthetic or ethical, as valuable as these factors are, but overwhelmingly it is essential to survival. We must protect insects out of self preservation. Insects provide so many ecological services from pollination to food for vertebrates like birds, to being essential in the process of cycling nutrients and energy.

Living in the USA at the moment, is to witness the triumph of the values of extreme capitalism over all other systems of value. The only system of value in place seems today or those of money and power, short term gain and making an overwhelmingly beneficial deal. The consequences of this intensely antisocial value system are reflected in ethical breakdown and the rise of authoritarianism, and this will have deep and pernicious results. Part of this culture of brute capitalism is also a breakdown in rationality and dismissal of long term research science. Without committed long term environmental research it is impossible to understand the scope of ecological degradation.

Part of the melancholic aspect of our entomologist is that the scope of environmental catastrophe is overwhelming. I read extensively on the subject of “the insect apocalypse” and became interested in a number of aspects of the situation. The first is that the phenomenon was first identified by amateurs rather then entomologists working for the state or a University or museum. I loved how this seemed like a bridge to old fashioned natural history study, where citizen science played such a huge role. Something else that was inspiring was how international and cooperative the discipline seems to be, with scientists and amateurs sharing information across the globe. I was very influenced by Elizabeth Kolbert’s profile of Dr. David Wagner, an insect biologist from University of Connecticut. Since so little good news is coming from the world of invertebrate studies, I imagined him as necessarily being melancholic. Ironically when I meet him he told me he was not melancholic but rather fired up and activated. He said now is the moment for action and engagement and there is not time for melancholy. While I agree, I also think mourning is an appropriate response for our moment and it definitely does not exclude action.

Chapter IV

Insects Food of the Future

PS: And what does your entomologist protagonist think when it is announced to him with tractousness that insects will be our food of the future?

What insects are we talking about? Considering that insects have declined by 80 percent in recent decades, and he knows that insects are the lynchpin of biodiversity: they are consumers and food for birds and reptiles, and without insects there would no longer be 70 percent of the plant species we know.

There are some who even in postmodernity call for the return of DDT to defeat the Anopheles mosquito in Africa, which is responsible for malaria.

MD: There have long been calls for insects to be used as food in the future. It seems to be a pretty narrow group of insects they consider for consumption, which includes crickets and grasshoppers. This may solve some human protein problems but it will have no impact on insect diversity issues, other then freeing up land now used for cattle and feed crops.

Considering the interconnectedness of things a sharp drop in any population of organisms is something to be concerned about. Other vertebrates subsistence on insect consumption- birds, fish, reptiles and quite a few mammals. Numerous plants depend of insect pollination. As you say, many insects are indicator species, giving us a glimpse into the wider environmental health of an ecosystem. When we are getting such clear feedback messages from the world around us, it is at our peril that we ignore it.

I don’t see a widespread return to DDT or at least not to the excesses of its previous use. The battle with the Anopheles Mosquito is a example of evolution in process. As we apply new technologies of exclusion, biological and chemical control the mosquito constantly evolves to thwart our efforts to extinguish it. While it is amazing to see how quickly evolution can work, this is serious since the mosquitoes transmit the organism which causes malaria which effects tens of thousands of people.

Chapter V

The Devil’s Garden

PS: Speaking of biodiversity and monocultures, in the highly human-risk rainforests of the Amazon, biodiverse areas par excellence, one sometimes comes across mysterious areas where biodiversity disappears, and only Duroia hirsuta trees stand there. Local people call these areas Devil’s garden. The responsibility for the monoculture of Duroia hirsuta lies not with an evil spirit but with a species of ant, the Mymelachista schumanni that nests in the Trunk of this tree, killing with lethal doses of formic acid every other plant species in these areas, thus the ant ensures its colony an abundant amount of nesting sites. A long-term benefit, considering that colonies of Mymelachista schumanni can live up to 800 years. Isn’t the behavior of the lemon ant awfully similar compared to our intensive agriculture? Could planet Earth live if it was turned into an immense Devil’s garden?

MD: Perhaps the question should be, would it be worth living on an earth which was only a Devil Garden. Maybe these ant colonies seem particularly frightening since we see ourselves, in our immense transformative power, reflected in them.

I am very drawn to ecological parables like the one about the Devil Garden. When I stated making the kind of work I do today, in the late 1980s, many of my sculptures and installations took such tales of ecological calamity as a starting point. This was pretty much the moment when the term Biodiversity was coming into popular use. It is such a beautiful and powerful idea, meaning the variety and variability of life on earth. I think discovering the notion of biodiversity somehow gave meaning to my practice of as an artist. With so many artist form my generation, it is easy to understand what we are against, being so critically focused, but it is not always easy to understand what we are for. I am for biodiversity.

The story of the Devil’s Garden is a great illustration of the unforeseen consequences of environmental destruction. Once something is degraded, and then left to recover, there is no guarantee what returns will be the same things the site started with. Something will come back, but probably not what was there before. The same is true for fisheries. If one takes all the fish, eventually something will return to fill the empty niche but not often exactly the same fish.

Chapter VI

Donald Trump insect unconscious

PS: These days there is much talk about Trump and his tariffs that rattle Markets from East to West, traversing the globe in a divisive sense. Wouldn’t it be wacky if your entomologist produced a dream of the body-horror genre, turning the controversial American president into an insect. What insect with a Latin name could be the one dreamed up by the unconscious creativity of the melancholy entomologist?

MD: It is an insult to the world of invertebrates to call Trump an insect. Even a virus does not deserve the indignity of comparison to the President. Much worst then body-horror fiction is the culture of sadism and injustice daily paraded on American screens.

Perhaps if we did need to give him a Latin binomial name it could be Necrophorus Rex. King of the Dead.

Thanks to Monica Rivera for her precious research

Special thanks to Strega del Castello

for having shared with us some of the secrets of her enchanted world